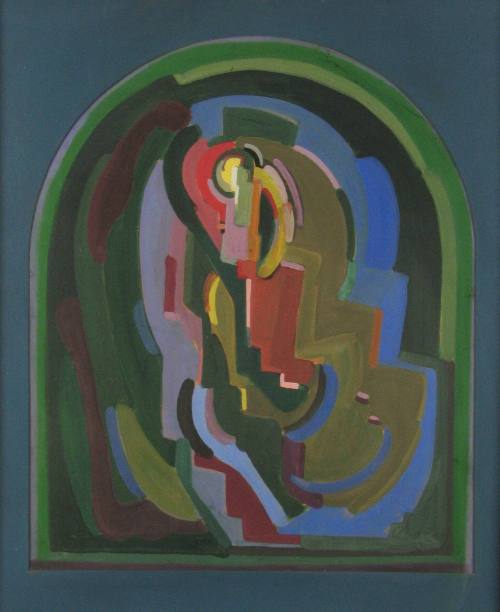

Abstract

Artist

Evie Sydney Hone

(1894 - 1955)

Date1925-1930

MediumGouache on paper

Dimensions65.8 x 55.3 cm

ClassificationsGouaches

Credit LineCollection & image © Hugh Lane Gallery.

Donated by the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland, 1973.

© The Estate of Evie Sydney Hone.

Object number1276

Description'My aim was to search into the inner rhythms and constructions of natural forms; to create on their pattern; to make a work of art a natural creation complete in itself, based on eternal laws of balanced harmony and ordered movement. I sought the inner principle and not the outward appearance.' Mainie JellettIn the first half of the 20th century Ireland’s leading artists, critics and intellectuals were concerned with the apparent lack of a distinctive Irish visual art tradition. In the decades from 1910 to 1940 Irish painting was dominated by images of the West of Ireland and of the Irish peasant heroically surviving amidst the primitive conditions of the Irish landscape and climate. When in 1923, the year after national Independence was declared, a young Irish woman artist, Mainie Jellett (1897-1944) exhibited the first abstract paintings to be seen in Dublin the work aroused a rather brutal reaction. Jellett was accused by the normally mild-mannered George Russell of suffering from artistic malaria. Her radical version of modernist art was identified as potentially debilitating and highly infectious. This extreme response, not typical of Irish art criticism, indicates the gulf which existed between the artistic language and intention of Jellett’s cubist inspired abstractions and that of the dominant figurative tradition associated with the drive for a national school of visual art. Her continentally inspired work was simply not relevant to the New Ireland. However within two decades Jellett and her friend, Evie Hone (1894-1955), were acknowledged as significant artists whose work was meaningful to its Irish audience.

Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone came from relatively privileged Anglo-Irish backgrounds. Hone was struck down by infant paralysis at the age of 11 and had profound difficulties with her health throughout her life. She spent much of her adolescence abroad. Jellett, the daughter of a barrister, attended the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin. Having studied art in London, both women enrolled in the atelier of André Lhote (1885-1962) in Paris. In going to France to complete their studies the women were following an established pattern, particularly amongst middle-class female artists, of working in the new privately run academies of Paris and other European cities. The opening up of such establishments in the mid 19th century provided ambitious females with the opportunity of escaping the confines of home life and of being able to study the life model, then the focus of academic and realist art. By the 1920s when Hone and Jellett lived in France modernism rather than realism predominated and Paris, the centre of the art world, provided direct exposure to this rarely seen or understood art practice.

Andre Lhote’s studio was recently opened when Jellett and Hone enrolled there in 1920. Jellett considered it to be ‘the most advanced public academy of the time’. Hone was advised to attend the school by her teacher at the Central School of Art in London, Bernard Meninsky. Jellett would have known of Lhote through his writings in La Nouvelle Revue Francaise, translations of which were published in the London art periodical, Athenaeum. Lhote had been associated with cubism since 1911 when the movement first came to wider public attention at the Salon des Indépendants exhibition in Paris. He had modernised his portraits, landscapes, still-lifes and scenes of everyday life through the use of a stylised cubist approach which was much more colourful and decorative than the original severe language of cubism developed by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in the years 1908-11. Like his fellow cubists Lhote continued to develop the style and argue for its relevance to art and society in the post World War One period.

Students at the atelier spent several hours a day drawing from the life model with Lhote critiquing their work one day a week. He encouraged the students to study the old masters and to familiarise themselves with different systems of perspective ranging from that of classical to Chinese art. Jellett later wrote that her and Hone’s time with Lhote had ‘opened our minds to a vast realm of research and riches in the Old Masters and showed us clearly how his teaching and ideals followed logically the living tradition based on permanent truths which are the heritage of all great art’. The connection between contemporary art practice and that of past artists was fundamental to the future development of both Jellett’s and Hone’s work and ideas.

Following in the footsteps of Jellett and Hone, and often encouraged by the artists to go there, several other Irish artists interested in exploring modernist art enrolled in Lhote’s studio in the 1920s and 1930s. The French painter’s palatable version of cubism which combined recognisable subject matter with decorative form was appealing. Its influence was very evident in the work shown at the Society of Dublin Painters, founded in 1920, where a small group of artists, mainly women, exhibited a more modernist style of art to that found in the Royal Hibernian Academy, the major exhibition forum of the period. (It was at the Society of Dublin Painters’ gallery that Jellett and Hone first exhibited their abstract paintings).

One of the first Irish artists to work with Lhote, after Jellett and Hone, was May Guinness (1863-1955), an older and more established artist than they. She studied with Lhote from 1922 to 1925, despite having already lived and worked in Paris over the previous ten years. Having painted in Brittany, she had worked as a nurse in the French army during World War One for which she was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Like many of Lhote’s Irish students, Guinness remained a figurative artist. She had worked with leading Fauve artists in Paris including Kees Van Dongen who encouraged the development of strong colours in her work. From Lhote she learned of the geometric construction of form gleaned from Cezanne and the cubists. Guinness’s determination to keep herself informed of developments in French painting was typical of Anglo-Irish women artists of this period. They had little interest in the more radical manifestations of modernism than emerging in Paris, such as Dada and Surrealism. The oppositional and often anti-feminist nature of this avant-garde art made it unsuited to the needs and goals of this group of Irish artists. However their fascination with the international cubist inspired language of form and colour indicates their need to offset the growing isolationism of post-Independence cultural life through a continuous engagement with wider European art. They were working and living within the peculiar contexts of a new state whose fledgling bourgeoisie aligned itself increasingly to a conservative Catholic outlook, in which the role of women was extremely curtailed. Anglo-Irish women artists chose to take a conciliatory attitude to this regime and were open in their art practice and activities rather than antagonistic.

In spite of his popularity with other artists, Jellett and Hone were not content with the limited version of modernist art expounded by Lhote. They quickly sought to expand their practice by working with a more challenging aesthetic, that of abstract art. In December 1921 they approached the reclusive artist, Albert Gleizes (1881-1953) and asked him to take them on as assistants. He was an unusual choice of mentor and apparently was rather taken aback by the appearance of these two young artists on his doorstep. As Jack Yeats later put it, ‘Who the blazes is Gleizes?’’ In fact Gleizes was well-known in avant-garde circles in France. He had been associated with the cubists since 1909, had participated in the famous 1911 Salon des Independants cubist room and had co-written the first history of the movement, Du Cubisme with Jean Metzinger in 1911. During the war Gleizes had lived in relative isolation in New York and upon his return to Paris had embarked on a new direction in his work. When Jellett and Hone worked with him, he was experimenting with an abstract art based on the cubist style. Like other pioneers of abstraction, such as Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian, Gleizes believed that art should be spiritual and non-materialist. Central to this concept was the rejection of three-dimensional space. Cubism had challenged Western art by using a perspective which related to the two dimensional world of the canvas rather than the outward view. Gleizes recognised that artists working prior to the Renaissance similarly neglected linear perspective. Like the cubist, the Byzantine or pre Renaissance artist was not interested in replicating reality.

The decision to work with Gleizes had a profound effect on the work of all three artists. Jellett described the atmosphere in the atelier as ‘like the old Italian studios, the master and students worked together, sometimes on the same painting. Each helped the other ...’. Gleizes later acknowledged the influence that the younger Irish artists had on the development and formulation of his ideas on art. The method of making this new type of abstract art was called Translation/Rotation. Gleizes explained it in his 1923 book, La Peinture at ses Lois (Painting and its Rules). The artist began with the basic shape of the canvas or board and painted the surface in one colour and then proceeded to select colours and shapes which echoed the form of the canvas. This was the static element of Translation. Next in Rotation the artist rotated these basic forms to create a dynamic composition which introduced the idea of time or movement into the composition. The latter was largely gleaned from cubism and Futurism. In his description of this new method Gleizes called for the reinstigation of rules in art. He noted that Byzantine artists were not free to follow their own whims when creating a work of art. Certain rules and conventions had to be observed. The same, Gleizes asserted, should be true for the modern artist.

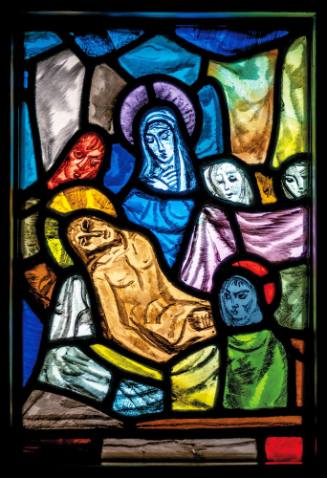

Gleizes’s ideas connected with those of Jellett and Hone on a number of fundamental levels. All three believed that art should serve a spiritual function as it had done in the past and thus were interested in exploring the connections between cubism and medieval painting. Secondly they were concerned with the idea of working collaboratively to produce art that would appeal to the wider public and contribute to society generally rather than to a specialist audience. Gleizes was an outspoken critic of the growing art market in Paris and its search for the latest style or fashion. He intended that abstract art would offer an avenue for a new spiritual art language. While this new aesthetic acknowledged the dramatic contribution of cubism it was not to become commercial. In the late 1920s Gleizes left Paris and set up a co-operative for artists at Moly Sabata in the Rhone valley devoted to religious mural painting. Finally all three were committed to the didactic role of the artist in explaining modern art and craft to others. Jellett and Gleizes wrote and lectured widely on modern art and on their own practice while Hone later ran the Tur Gloine stained glass studios and committed herself to religious art which would be displayed within churches rather than art galleries.

The initial intense time of experimentation that Jellett and Hone spent with Gleizes ended in 1923 when Jellett returned to Dublin. But both she and Hone made regular visits back to France where they continued to work with Gleizes. Their decision to return to Ireland rather than pursue careers abroad is significant. Both wanted to contribute to the development of visual art in Ireland. Largely thanks to the negative reception of her work, Jellett quickly became the spokesperson for modernism in Ireland, lecturing widely on various aspects of the subject. She took on private pupils and gave summer sketching classes, encouraging younger artists to engage with modern art. In 1943 she was instrumental in the setting up of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, a major alternative exhibition forum to the RHA, at which a wide range of modernist art was shown. Jellett was briefly chairman of the Living Art before her early death in 1944.

The connection with pre-Renaissance art, evident in the choice of compositions and colours made by both Hone and Jellett, became more obvious as their work progressed. They moved from an extreme abstraction in the mid 1920s to a more figurative treatment with Jellett giving religious titles to her works from the late 1920s onwards. Hone abandoned painting and concentrated on stained glass. Converting to Catholicism in 1937, she became one of Ireland’s most acclaimed religious artists. The retreat from abstraction and the commitment to religious subject matter made Jellett’s work increasingly acceptable to an Irish audience. Her art offered a universal artistic language which was both modern and spiritual and thus combined two key elements in the state’s cultural self-image. Both Jellett and Hone were commissioned by the government to produce work for international exhibitions in the late 1930s where their modern aesthetic presented Ireland as forward thinking and sophisticated. In these commissions the gulf between the universal forms of art and the more immediate needs of national culture was partly bridged.

Jellett and Hone’s more interesting work, like the examples in this exhibition, is intimate and experimental. Their abstract-cubist painting does not make grand didactic statements. As Jellett described it, ‘The picture is organised as a natural creation, it is like a small universe, controlled by a defined rhythmic movement within a given space.’ This austere language of abstract form and colour, so baffling to its first audience, can now be seen as part of the utopian project of modernism. It represents a pioneering engagement with the language of painting, both ancient and modern. It combines the mystery of medieval icons with the dynamism of cubism, in a quest for the ‘inner principle’, as Jellett described it. For the contemporary viewer the real value of this work may lie in its search for, rather than its finding of, this allusive principle. The rigorous nature of the aesthetic is offset by the intuitive way in which colour and form is used by each artist. The works are subtle balancing acts between harmony and movement which resonate with a belief in the expressive power of art.

Dr Roisín Kennedy

(From: The Collection Revealed: Cubism 11 June - 20 September 2009. Curated by Jessica O'Donnell. ISBN 978-1-901702-34-7)

On View

Not on viewEvie Sydney Hone